Sierra Madre Villa Bike Lanes

When local governments do little to make their cities bike and pedestrian friendly, I have often been quick to criticize. Sometimes I do a lot of criticizing, because so much still needs to change to enable the transition to a healthier, safer, more sustainable, more equitable transportation system. But when cities do the right thing, as Pasadena did last week, I want to give credit where it’s due and offer fulsome praise in the hopes that it encourages additional positive steps. Sometimes both happen at the same time, and thus my praise will be tempered with some constructive criticism.

The good:

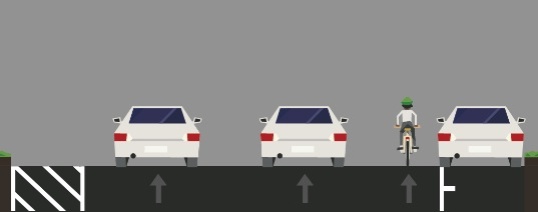

Pasadena recently painted new buffered bike lanes on Sierra Madre Villa in east Pasadena between Foothill and Orange Grove north of the Gold Line Station. This road diet improves safety along a notorious stretch of road, and provides buffered space for cyclists to ride to and from the retail and residential zones to the north of the station. Some may recall that this blog has called for a road diet on this street, so it is nice to see the city make this street safer for all.

This safety improvement is especially important with the Metro Bike bikeshare program set to expand into Pasadena. The retail area is still way too car-centric and these lanes abruptly end at Foothill and Orange Grove, limiting their usefulness for those who might not feel confident riding on those busy surrounding streets, but it is most definitely a step in the right direction, and Pasadena DOT and Councilmember Gene Masuda are to be complimented for their support for this project.

If bike lanes are extended north to Sierra Madre Blvd and South to Colorado Bl. extended east and west on Orange Grove and Rosemead Bl., a network of bike-friendly streets would exist for the first time in east Pasadena. Once this happens, the area would become bikeable not only for self-identified “cyclists,” but for everyone. There is much latent demand for bike friendly streets in east Pasadena. There are parks, schools, offices, and a major shopping/dining area nearby. With the eventual addition of more transit-oriented development (TOD) around the Sierra Madre Villa Gold Line Station, the demand for walkable, bikeable streets in this part of Pasadena will likely grow.

The Bad:

Despite improvements such as Sierra Madre Villa, Pasadena still lacks a connected network of bike-friendly streets. Riding on N. Hill in central Pasadena recently (see photo), within the space of two blocks I was aggressively passed by two motorists, one of whom impatiently honked at me for good measure. I was legally riding on the right half of the right-hand lane, but there is no bike infrastructure on north-south streets in this part of town, and the low-level aggression from motorists makes the experience unpleasant for anyone on a bike.

I brushed the incidents off as a “normal” part of riding in the city (I even gave the honking motorist a friendly wave), but the city cannot expect most people to feel comfortable on streets where they may be subject at any moment to vehicular harassment—or worse. The only way to accomplish this is to create a contiguous network of complete streets, well marked and intuitive to follow. This network must allow people to get to desirable destinations safely on foot or by bike.

Yes, education, encouragement, and enforcement are elements of a bike-friendly city, and I don’t suggest ignoring those, but the contrast between the streets with and without bike lanes shows there is no substitute for bike and pedestrian friendly infrastructure. In short, good things are happening in Pasadena, but we still have a way to go before city officials can claim city streets are “bike friendly.”